The Rich Don’t Flee, They Bluff

Across the US, UK, and France, governments are revisiting how to tax extreme wealth, ranging from property to unrealized gains to corporations. The motives differ—some seek fairness, others fiscal survival—but the anxiety is the same: If we tax the rich, will they leave?

A significant body of research suggests that they will not. But this question has come into sharper focus as Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani prepares to take office after months of the richest New Yorkers suggesting that they’ll pick up and leave if he succeeds at raising the corporate tax rate and adding a new 2 percent tax on millionaires.

Yet, before debating who might leave, it’s worth asking: Why are these taxes needed in the first place?

While Mamdani’s proposals are also pitched to fund vital government services, it is ever-widening wealth inequality that has kept federal tax reform on the docket.

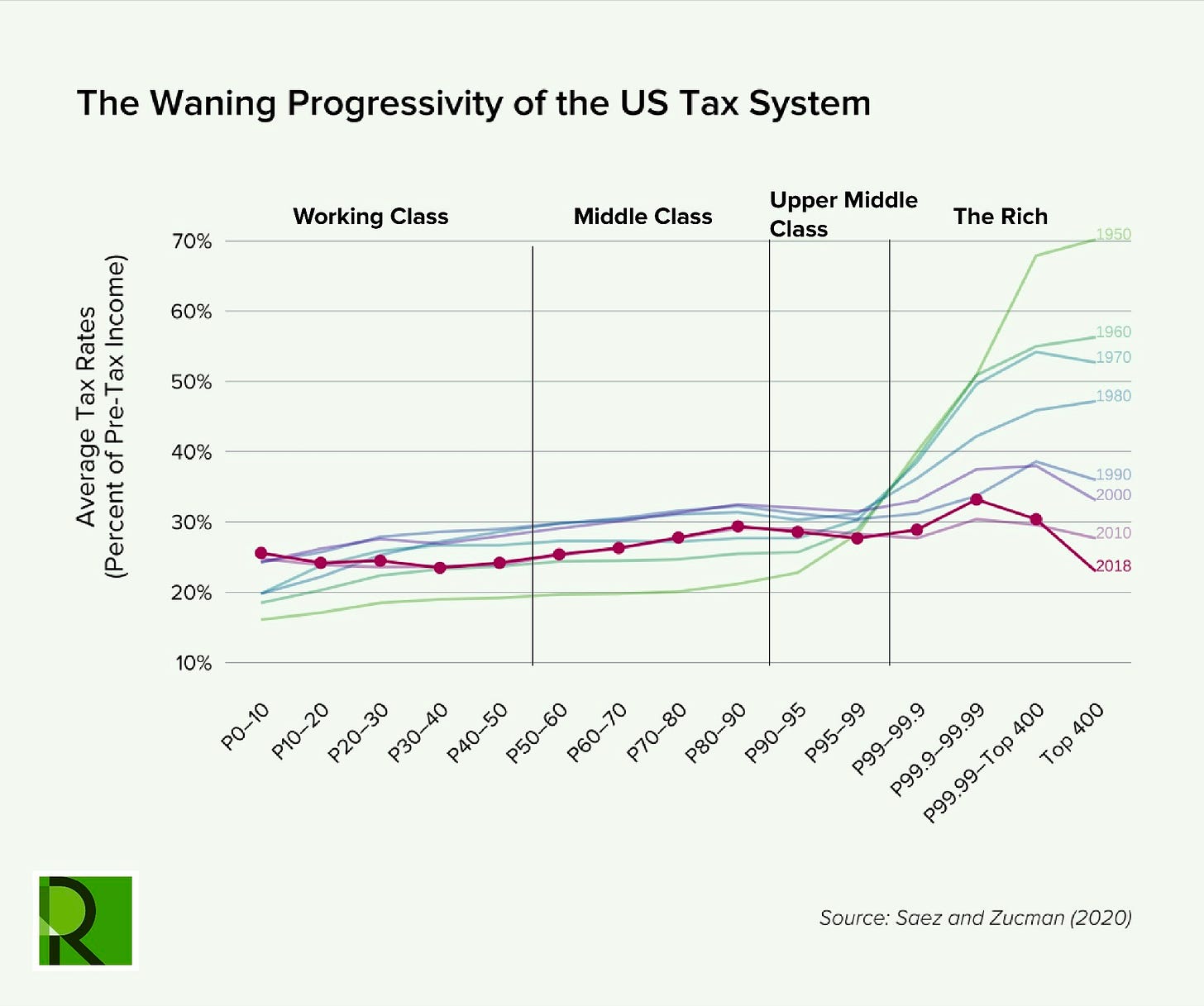

Between 2018 and 2020, the top 400 earners in the US paid an average of 24 percent of every dollar earned in tax. This is significantly less than the national average tax rate of 30 percent—and even lower than what many middle- and working-class Americans pay. Regressive tax reforms, like President Donald Trump’s recent budget reconciliation bill, increased taxes for the poorest Americans while lowering them for the richest.

The result is an average tax rate that is progressive until the very top of the distribution, where it starts bending down, as shown below.

This ultra-wealthy class of individuals—the top 0.1 or even 0.01 percent—earns in a very different way than the median earner. Most of their income comes from capital, including pass-through business income, capital gains, dividends from stocks, and rent—compared with almost everyone else, who mostly earn income through labor. Income derived from capital is generally taxed at a lower rate compared to labor income, leading top earners to face a very different tax landscape.

Jeff Bezos, for instance, paid himself a little over $80,000 per year as Amazon’s CEO, because, in his words, “I just didn’t feel good about taking more.” The move likely saved him millions in taxes: ProPublica analysis of leaked tax records from 2014 to 2018 estimated Bezos’s own personal federal tax rate at less than 1 percent, compared with the top federal tax rate of 37 percent. He likely avoided that top rate again this past July when he sold $666 million of Amazon stock, a transaction subject to the 23.6 percent capital gains rate with no state tax at all, since he lives in Florida (an intentional move on Bezos’s part, which supports the argument for higher federal rates).

The Fear That Shapes Our Tax Debates

Any discussion of tax must, however, engage with the idea of distortion—that is, the potential for taxes to change behavior by altering incentives. And one particular distortion seems to dominate every debate: capital flight.

The rich pay a large share of total taxes, even if their average rates can be low; the top 1 percent of Americans (earning $663k or more in 2022) paid 40 percent of all income tax in 2022. If these taxpayers left, the story goes, their absence would reduce the overall tax base, undermining essential government services.

If the goal of a government is to address rising inequality, however, then a tax that raises exactly as much revenue as it loses through tax flight would be a good policy if it reduces the wealth gap while remaining revenue neutral. A tax that shrinks the tax base may also be acceptable, if a government is willing to “spend” money in the form of reduced revenue.

For cash-strapped countries, this trade-off is less palatable, but it becomes more viable during periods of high growth. So, what weight should we give to threats by billionaires to leave in response to tax reform, as they have been making in New York since Mamdani’s election?

Research from the Fiscal Policy Institute highlights just how sticky location preferences can be. Their report found no evidence of an increase in mobility among the rich in response to city tax increases in 2017 and 2021. In general, the top 1 percent of New York’s earners migrate at one-quarter of the rate of the rest of the population. And when they do move, it is disproportionately to other high-tax states like Connecticut, California, and New Jersey.

If anything, research suggests that it is the middle class who are leaving New York, and the affordability crisis seems to be a stronger push factor than tax. Households with young children are more than twice as likely to move out of New York City, and 36 percent of households leaving the state cited unaffordable housing as the reason. We will be able to measure the actual extent of wealth flight in time, but some of Andrew Cuomo’s high-profile backers are already striking a more conciliatory tone.

Willingness to move is context dependent, yes, but wider evidence supports the conclusion that even outside of New York City this is not as serious a problem as many fear. Relatively few may actually be prepared to become former New Yorkers.

Moreover, after a millionaire’s tax in Massachusetts and a capital gains hike in Washington in 2022, the number of millionaires actually grew by 39 and 47 percent respectively, with the taxes raising billions for those states.

And outside the US, a new paper analyzes Scandinavian administrative data, the gold standard in empirical economics research. While the authors found modest evidence of mobility (perhaps aided by the free movement of people and capital within the EU’s common market), only 20 cents of every dollar raised by the new tax was lost to capital flight. It would have needed much larger migration responses than those observed for the taxes not to raise substantial revenue.

This new work suggests previous findings that people are reluctant to migrate apply to the rich as well. The authors note that distortions of a tax—changes to savings and investment decisions, and a rise in avoidance and evasion—are more important than migration threats.

How to Tax Without Fear

Certain policy levers can mitigate migration. The US is one of the only countries to apply its full tax code internationally on the basis of citizenship and not only residence. This creates a stronger disincentive to leaving, which other countries could emulate. Coordination could also help. The US could (re)join 130 other countries that have agreed to minimum global corporate tax rates, and one could imagine a similar agreement targeting high-net-worth individuals too.

Yet, the myth of millionaire mobility has done its job: It’s made policymakers nervous and kept billionaires comfortable. The evidence tells a simpler story—most of them stay put.

Several serious reforms are being discussed, including changing capital gains or estate taxes; introducing new measures such as wealth taxes on unrealized gains, land taxes, or consumption taxes; or even a more holistic reform of the tax system. The first challenge, however, shouldn’t be figuring out whether the rich will flee; it’s whether we’ll finally stop letting that fear write our tax policy.

Fireside Stacks is a weekly newsletter from Roosevelt Forward about progressive politics, policy, and economics. If you enjoyed this installment, consider sharing it with your friends.